A brief introduction to the GNU Autotools

This is a book originally published on Free Software magazine, I reedit it to make it more comfortable to read. This is Chapter 1.

Autotools: a practitioner’s guide to Autoconf, Automake and Libtool

------ Below is the book ------

Chapter 1: A brief introduction to the GNU Autotools

I’m going to make a rather broad and sweeping statement here: If you’re writing free or open source software targeting Unix or Linux systems, then you should be using the GNU Autotools. I’m sure I sound a bit biased, but I’m not. And I shouldn’t be, given the number of long nights I’ve spent working around what appeared to be shortcomings in the Autotools system. Normally, I would have been angry enough to toss the entire project out the window and write a good hand-coded makefile and configure script. But the one fact that I always came back to was that there are literally thousands of projects out there that appear to be very successfully using the Autotools. This was too much for me. My pride would never let me give up.

Who should use the Autotools?

The Autotools are supposed to make projects simpler for the maintainer, right? And the answer to that question is a definitive “No”. Don’t misunderstand me here–the Autotools do make your life easier in the long run, but for different reasons than you may first realize. The primary goal of the Autotools is not to make project maintenance simpler, although I honestly believe the system is as simple as it can be, given the functionality it provides. It took me a while to figure this out, and really, it was one of my most significant Autotools epiphanies. Ultimately, I came to understand that the purpose of the Autotools is two-fold: First, to make life easer for your users, and second, to make your project more portable–even to systems on which you’ve never tested, installed or even built your code.

Well then, what if you don’t work on free or open source software? Do you still care about these goals? What if you’re writing proprietary software for Unix or Linux systems? Then, I say, you would probably still benefit to some degree from using the Autotools. Even if you only ever intend to target a single distribution of Linux, the Autotools will provide you with a build environment that is flexible enough to allow your project to build successfully on future versions or distributions with virtually no changes to the build scripts. And, let’s be honest here–you really can’t know in advance whether or not your management will want your software to run on other platforms in the future. This fact alone is enough to warrant my statement.

Who should Not use the Autotools?

About the only scenario where it makes sense NOT to use the Autotools is the one in which you are writing software for non-Unix platforms only–Microsoft Windows comes to mind. Some people will tell you that the Autotools can be used successfully on Windows as well, but my opinion is that the POSIX/FHS approach to software build management is just too alien for Windows development. While it can be done, the tradeoffs are way too significant to justify shoe-horning a Windows project into the Autotools build paradigm.

I’ve watched some project managers develop custom versions of the Autotools which allow the use of all native Windows tools. These projects were maintained by people who spent much of their time tweaking the tools and the build environment to do things it was never intended to do, in a hostile and foreign environment. Quite frankly, Microsoft has some of the best tools on the planet for Windows software development. If I were developing a Windows software package, I’d use Microsoft’s tools exclusively. In fact, I often write portable software that targets both Linux and Windows. In these cases, I maintain two separate build environments–one for Windows, and one based on the Autotools for everything else.

The original reasons for using GNU tools to build Windows software were that GNU tools were free, and Microsoft tools were expensive. This reason is no longer valid, as Microsoft makes the better part of their tools available for free download today. This was a smart move on their part–but it took them long enough to see the value in it.

Your choice of language

One other important factor in the decision to use or not use the Autotools with your project is your language of choice. Let’s face it, the Autotools were designed by GNU people to manage GNU projects. There are two factors that determine the importance of a computer language within the GNU community:

- Are there any GNU packages written in the language?

- Does the GNU compiler tool set support the language?

Autoconf provides native support for the following languages based on these two criteria:

- C

- C++

- Objective C

- Fortran

- Fortran 77

- Erlang

By “native support”, I mean that Autoconf will compile, link and run source-level feature checks in these languages.

If you want to build a Java package, you can configure Automake to do so, but you can’t ask Autoconf to compile, link or run Java-based checks. Java simply isn’t supported natively at this time by Autoconf. I believe it’s important to point out here that the very nature of the Java language and virtual machine specifications make it far less likely that you’ll need to perform a Java-based Autoconf check in the first place.

There is work being actively done on the gcj compiler and tool set, so it’s not unreasonable to think that some native Java support will be added to Autoconf at some future date, but gcj is a bit immature yet, and currently very few (if any) GNU packages are written in Java, so the issue is not critical to the GNU community.

That said, there is currently rudimentary support in Automake for both GNU (gcj) and non-GNU Java compilers and VM’s. I’ve used it myself on a project, and it works well, as long as you don’t try to push it too far. Given the history of the GNU project, I think it’s safe to say that this functionality will definitely improve with age.

If you’re into Smalltalk, ADA, Modula, LISP, Forth, or some other non-mainstream language, well then you’re probably not too concerned about porting your code to dozens of platforms and CPUs.

As an aside, if you are using a non-mainstream language, and you are in fact concerned about the portability of your build systems, then please consider adding support for your language to the Autotools. This is not as daunting a task as you may think, and I gaurantee that you’ll be an Autotools expert when you’re finished. If you think this statement is funny, then consider how Erlang support made it into the Autotools. I’m betting most developers have never heard of Erlang, but members of the Erlang community thought it was important enough to add Erlang support themselves.

Generating your package build system

The GNU Autotools framework is comprised of three main packages, each of which provides and relies on several smaller components. The three main packages are Autoconf, Automake and Libtool. These packages were invented in that order, and evolved over time. Additionally, the tools in the Autotools packages can depend on or use utilities and functionality from the gettext, m4, sed, make and perl packages, as well as others.

It’s very important at this point to distinguish between a maintainer’s system and an end-user’s system. The design goals of the Autotools specify that an Autotools-generated build system rely only on readily available, preinstalled tools on the host machine. Perl is only required on machines that maintainers use to create distributions, not on end-user machines that build packages from resulting release distributions packages. A corollary to this is that end-users’ machines need not have the Autotools installed.

If you’ve ever downloaded, built and installed software from a “tarball”–a compressed archive with a .tar.gz, .tgz or .tar.bz2 extension–then you’re probably aware of the fact that there is a common theme to this process. It usually looks something like this:

$ gzip -cd hackers-delight-1.0.tar.gz | tar -xvf -

...

$ cd hackers-delight-1.0

$ ./configure

$ make all

$ sudo make installNOTE: I have to assume some level of knowledge on your part, and I’m stating right now that this is it. If you’ve performed this sequence of commands before and you know what it means, and if you have a basic understanding of the software development process, then you’ll have no trouble following the content of this book.

Most developers know and understand the purpose of the make utility. But what’s the point of the configure script? The use of configuration scripts (generally named configure) started a long time ago on Unix systems due to the variety imposed by the fast growing and divergent set of Unix and Unix-like platforms. It’s interesting to note that while Unix systems have generally followed the defacto-standard Unix kernel interface for decades, most software that does anything significant generally has to stretch outside of these more or less standardized boundaries. Configuration scripts are hand-coded shell scripts designed to determine platform-specific characteristics, and to allow users to choose package options before running make.

This approach worked well for decades. With the advent of dozens of Linux distributions, the explosion of feature permutations has made writing a decent portable configuration script very difficult–much more so than writing the makefiles for a new project. Most people have come up with configuration scripts for their projects using a well-understood and pervasive technique–copy and modify a similar project’s script. By the early 90’s it was becoming apparent to many developers that project configuration was going to become painful if something weren’t done to ease the burden of writing massive shell scripts to manage configuration options–both those related to platform differences, and those related to package options.

Autoconf

Autoconf changed this paradigm almost overnight. A quick glance at the AUTHORS file in the Savannah Autoconf project repository will give you an idea of the number of people that have had a hand in the making of Autoconf. The original author was David MacKenzie, who started the Autoconf project in 1991. While configuration scripts were becoming longer and more complex, there were really only a few variables that needed to be specified by the user. Most of these were simply choices to be made regarding components, features and options: Where do I find libraries and header files? Where do I want to install my finished product? Which optional components do I want to build into my products? With Autoconf, instead of modifying, debugging and losing sleep over literally thousands of lines of supposedly portable shell script, developers can write a short meta-script file, using a concise macro-based language, and let Autoconf generate a perfect configuration script.

A generated configuration script is more portable, more correct, and more maintainable than a hand-code version of the same script. In addition, Autoconf often catches semantic or logic errors that the author would have spent days debugging. Another benefit of Autoconf is that the shell code it generates is as portable as possible between systems that supply any form of the Bourne shell. Mistakes made in portability between shells are by far the most common, and unfortunately the most difficult to find, because no one programmer has access to all versions or brands of Bourne-like shells in existence.

Autoconf generated configure scripts provide a common set of options that are important to all portable, free, open source, and proprietary software projects running on LSB-compliant systems. These include options to modify “standard locations”, a concept I’ll cover in more detail in Chapter 2. Autoconf generated configure scripts also provide project-specific options. These are defined in the configure.ac file for each project. I’ll detail this process in Chapter 3.

The Autoconf package provides several programs. Autoconf itself is written in Bourne shell script, while the others are perl scripts.

- autoconf

- autoheader

- autom4te

- autoreconf

- autoscan

- autoupdate

- ifnames

Autoheader

The autoheader utility generates a C language header file template from configure.ac. This template file is usually called config.h.in. We’ll cover autoheader in greater detail in Chapter 3.

</h4>Autom4te</h4>

The autom4te utility is a cache manager used by most of the other Autotools. In the early days of Autoconf there was really no need for such a cache, but because most of the Autotools use constructs found in configure.ac, the cache speeds up access by successive programs to configure.ac by about 40 percent or more. I won’t spend a lot of time on autom4te (which is pronounced “automate”, by the way), because it’s mainly used internally by the Autotools, and the only sign you’re given that it’s working is the existence of an autom4te.cache directory in your top-level project directory.

Autoreconf

The autoreconf program can be used to execute the configuration tools in the Autoconf, Automake and Libtool packages as required by the project. The purpose of autoreconf is to minimize the amount of regeneration that needs to be done, based on timestamps, features, and project state. Think of autoreconf as an Autotools bootstrap utility. If all you have is a configure.ac file, running autoreconf will run the tools you need in order to run configure and then make.

Autoscan

The autoscan program is used to generate a reasonable configure.ac file for a new project. We’ll spend some time on autoscan later in Chapter’s 3 and 6, as we go through the process of setting up the Autotools on a basic project.

Autoupdate

The autoupdate utility is used to update your configure.ac or template (*.in) files to the syntax of the current version of the Autotools. I’ll cover autoupdate in more detail in Chapter 2.

Ifnames

The ifnames program is a small, and generally under-utilized program that accepts a list of source files names on the command line, and displays a list of C preprocessor definitions and their containing files on the stdout device. This utility is designed to help you determine what to put into your configure.ac and Makefile.am files for the sake of portability. If your project has already been written with some level of portability in mind, ifnames can help you find out where those attempts are located in your source tree, and what the names of potential portability defintions might be.

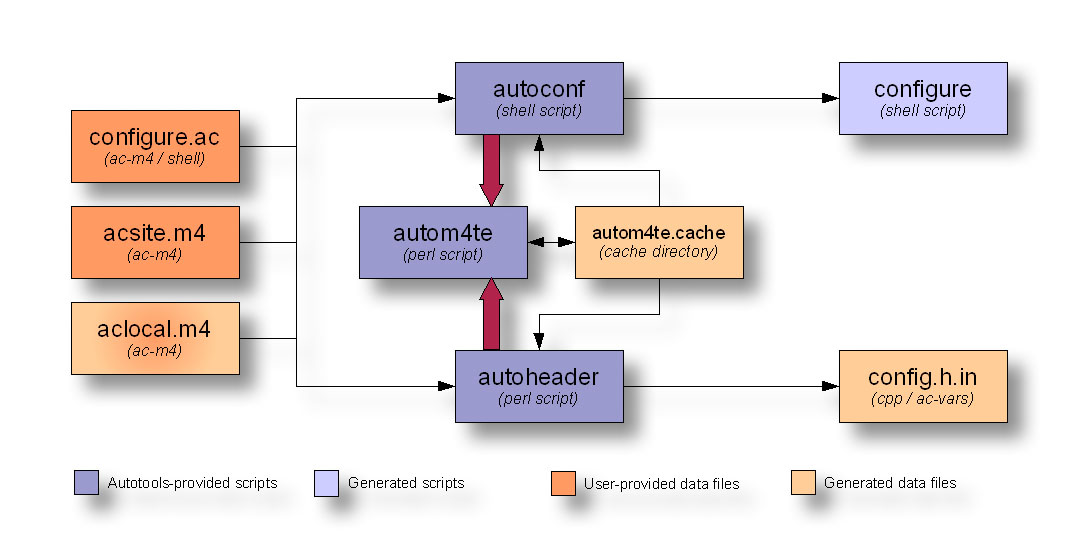

Of the tools in this list, only autoconf and autoheader are used directly by the project maintainer while generating a configure script, and actually, as we’ll see later, only autoreconf really needs to be called directly. The following diagram shows the interaction between input files and the Autoconf and autoheader programs to generate product files:

Figure 1: Autoconf and autoheader data flow diagram

NOTE: I’ll follow this data flow diagram format through the rest of this book. Darker colored boxes represent objects that are provided either by the user or by an Autotools package. Lighter shades of the same colors represent generated objects of the same type.

These tools’ primary task is to generate a configure script that can be used by you or others to configure a project build directory. The configure script generated does not rely in any way on the Autotools themselves. In fact, Autoconf is specifically designed to generate configure scripts that will run on all Unix or Unix-like platforms that support a Bourne shell. You should be able to generate a configure script from Autoconf, and then successfully execute that script on a machine which does not have the Autotools installed. Not surprisingly, this is actually a common use-case in the free software world, so it’s also a well-tested use case.

As you can see in this diagram, Autoconf and autoheader are called by the user. These tools take their input from your project’s configure.ac file, and various Autoconf-flavored m4 macro definition files. They use autom4te to maintain cache information. Autoconf generates your configure script, a very portable Bourne shell script that provides your project with configuration capabilities. Autoheader generates the config.h.in template based on macro definitions in configure.ac.

You may have noticed the apparent identity crisis being suffered by the aclocal.m4 input file. Is that a bit of a blush on that box–is it a generated file, or a user-provided file? Well, the answer is that it’s both, and I’ll explain this in more detail in the next section.

Automake

So, what’s so difficult about writing a makefile? Well, actually, once you’ve done it a few times, writing a basic makefile for a new project is really rather trivial. The problems occur when you try to do more than just the basics. And let’s face it–what project maintainer has ever been satisfied with just a basic makefile?

The single most significant difference between a successful free software project and one that rarely gets a second glance can be found deep in the heart of project maintenance details. These details include providing the so-called “standard make targets”. Potential users become disgusted with a project fairly easily–especially when certain bits of expected functionality are missing or improperly written. Users have come to expect certain more or less standard make targets. A make target is a goal specified on the make command line:

$ make installIn this example, install is the goal or target. Common make targets include all, clean and install, among others. You’ll note that none of these are real targets. A real target is a file produced by the build system. If you’re building an executable called doofabble, then you’d expect to be able to type:

$ make doofabbleThis would generate an actual executable file called doofabble. But specifying real targets on the make command line is more work than necessary. Each project must be built differently–make doofabble, make foodabble, make abfooble, etc. Why not just type make or make all, if there is more than one binary to be made? So all has become an expected pseudo-target, but “expected” doesn’t mean “automatic”.

Supporting the expected set of standard targets can be fairly challenging. As with configuration scripts, the most widely used implementation is one written in the late 80’s and copied from project to project throughout the internet. Why? Because writing it yourself is error prone. In fact, copying it is just as error-prone. It’s like getting a linked-list implementation right the first time. The process is well-understood by any veteran software engineer, but it still rarely happens. Object-oriented programming languages like C++ and Java provide libraries and templates for these constructs now–not because they’re hard to implement by hand, but because doing so is error-prone, and there’s no point in re-inventing the wheel–yet again.

Automake’s job is to convert a much simplified specification of your project’s build process into standard boilerplate makefile syntax that always works correctly the first time, and provides all the standard functionality expected of a free software project. In actuality, Automake creates projects that support guidelines defined in the GNU Coding Standards, which I’ll cover in greater detail in Chapter 2.

The Automake package provides the following tools in the form of perl scripts:

- automake

- aclocal

The primary task of the Automake program is to generate standard makefile templates (named Makefile.in) from high-level build specification files (named Makefile.am). One of the most interesting and useful aspects of the way Automake works is that the Makefile.am input files are mostly just regular makefiles. If you put only the few required Automake definitions in a Makefile.am, you’ll get a Makefile.in file containing several hundred lines of makefile code. But if you add additional makefile syntax to your Makefile.am files, this code will be transferred to the most functionally correct location in the resulting Makefile.in. In fact, you can (if you wish) write pure make syntax in your Makefile.am files, and they’ll work just fine (as long as you actually write them correctly, that is). This pass-through feature gives you the power and flexibility to extend Automake’s functionality with your project’s own special requirements.

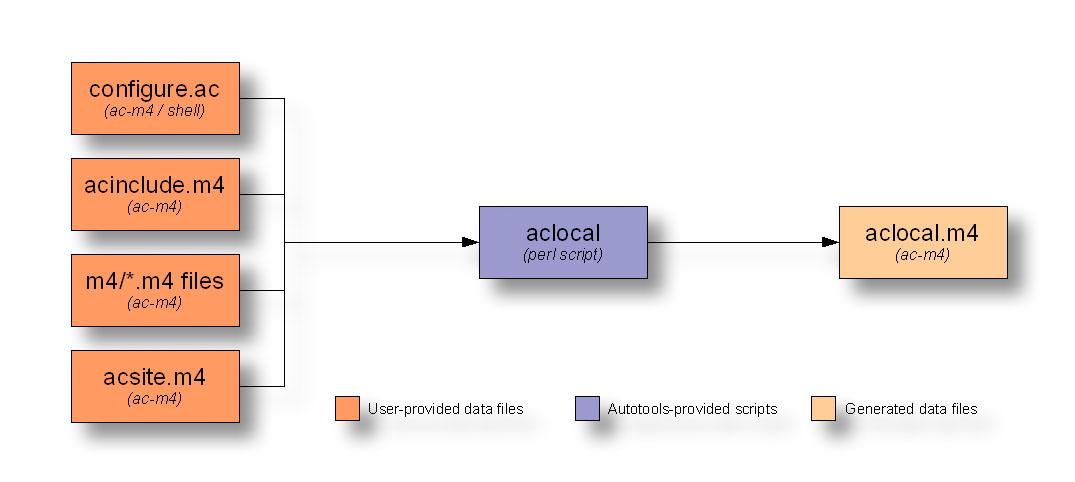

Aclocal

The aclocal utility is actually documented by the GNU manuals as a temporary work-around for a certain lack of flexibility in Autoconf. Autoconf was designed and written first, and then a few years later, the idea for Automake was conceived as an add-on for Autoconf. But Autoconf was really not designed to be extensible on the scale required by Automake.

Automake adds an extensive set of macros to those provided by Autoconf. The originally documented method for adding user-defined macros to an Autoconf project was to create a file called aclocal.m4 in the same directory as configure.ac. Any user-provided extension macros were to be placed in this file, and Autoconf would automatically read it while processing configure.ac. From the perspective of the Automake designers, this existing extension mechanism was too good to pass up. But requiring the user to add an m4_include line to aclocal.m4 seemed a bit brittle. Instead, the aclocal utility was designed to create a project’s aclocal.m4 file, containing all the required Automake macros. Since Automake’s aclocal utility basically took over aclocal.m4 for its own purposes, it was also designed to read a new user-provided macro file called acinclude.m4.

Essentially, aclocal’s job is to create an aclocal.m4 file by consolidating various macro files from installed Autotool packages and user-specified locations, such that Autoconf can find them all in one place.

For the sake of modularity, the Autoconf manual is still unaware of the aclocal utility–for the most part. The current revision of the manual rants a bit on the subject of where aclocal functionality should actually be. Automake’s manual originally suggested that you should rename aclocal.m4 to acinclude.m4 when adding Automake to an existing Autoconf project. This method is still followed rigorously in new projects.

However, the latest documentation from both sets of tools suggests that the entire aclocal/acinclude paradigm is now obsolete, in favor of a newer method of specifying a directory containing m4 macro files. The current recommendation is that you create a directory in your project directory called simply m4 (acinclude seems more appropriate to this author), and add macros in the form of individual .m4 files to this directory. All files in this directory will be gathered into aclocal.m4 before Autoconf processes your configure.ac file. Ultimately, aclocal will be replaced by functionality in Autoconf itself. (Given the fairly complex nature of aclocal functionality, and given that most of the other tools are already written in perl, I’m guessing that Autoconf will be rewritten in perl, at this point.)

Figure 2: Aclocal data flow diagram

With aclocal behind us, it should be more apparent now why the aclocal.m4 box in the Autoconf data flow diagram of Figure 1 above couldn’t decide which color it should be. When used without Automake and Libtool, the aclocal.m4 file is written by hand, but when used in conjunction with Automake and Libtool, the file is generated by the aclocal utility, and acinclude.m4 is used to provide project-specific macros.

Libtool

How do you build shared libraries on different Unix platforms without adding a lot of very platform-specific conditional code to your build system and source code? This is the question that the Libtool package tries to address.

There’s a significant amount of visible functionality in Unix and Unix-like platforms that is the same from one platform to another. However, one very significant difference is how shared libraries are built, named and managed. Some platforms don’t even provide native shared libraries (although it’s rare these days). Some platforms name their libraries libsomething.so, while others use something.o. Some use libsomething.a, while others use libsomething.sa. Some platforms provide libdl (dlopen/dlsym/dlclose) to allow software to dynamically load and access library functionality at runtime. Others provide other mechanisms–or none at all.

All of these differences have been carefully considered by the authors of the Libtool project. Dozens of platforms are currently supported by Libtool, and adding support for new platforms is done via the open source way–someone who cares (and knows how) supplies a patch to the Libtool mailing list, and the maintainers look it over and apply it to the source code for the next release.

Libtool not only provides a set of Autoconf macros that hide library naming differences in makefiles, but it also provides an optional library of dynamic loader functionality that can be added to your programs, allowing you to write more portable runtime dynamic shared object management code.

The libtool package provides the following programs, libraries and header files:

- libtool (program)

- libtoolize (program)

- ltdl (static and shared libraries)

- ltdl.h (header)

The libtool shell script is a generic version of Libtool designed to be used by programs on your platform. There’s nothing specific to a project in this particular copy of libtool.

Libtoolize

The libtoolize shell script is used to prepare your project to use Libtool. In reality, libtoolize generates a custom version of the libtool script in your project directory. This script is then executed at the appropriate time by Automake-generated makefiles.

The Libtool C API--ltdl

The Libtool package also provides the ltdl library and header files, which provide a consistent run-time shared object manager across platforms. The ltdl library may be linked statically or dynamically into your programs, giving them a consistent runtime shared library access interface from one platform to another.

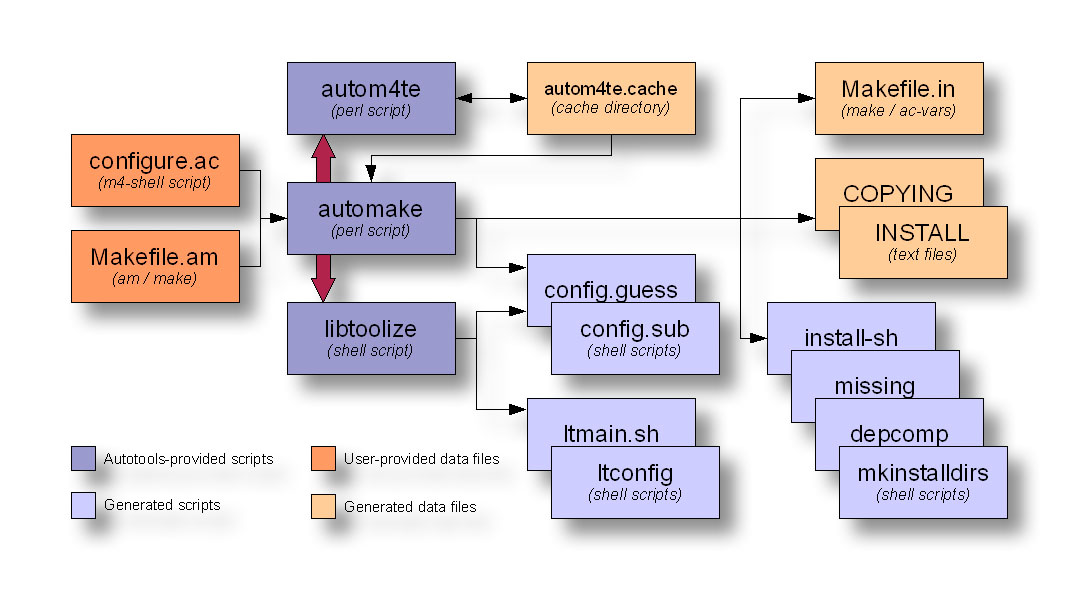

The following data flow diagram illustrates the interaction between Automake and Libtool scripts and input files to create products used by users to configure and build your project:

Figure 3: Automake and Libtool data flow diagram

Automake and Libtool are both standard pluggable options that can be added to configure.ac with a few simple macro calls.

Building your package

While, as maintainer, you probably build your software packages a lot more often than do your users, you also have the advantage of being intimately familiar with your project’s components, architecture and build system. That’s why you ought to be concerned that your users’ build experience is much simpler than yours. (And it wouldn’t hurt a bit if you got some benefit from this concern, as well.)

Running configure

Once the Autotools have finished their work, you’re left with a shell script called configure, and one or more Makefiles.in files. These product files are intended to be packages with project release distribution packages. Your users download these packages, unpack them, and run configure and make. The configure script generates Makefiles from the Makefile.in files. It also generates a config.h header file from the config.h.in file built by autoheader.

So why didn’t the Autotools just generate the makefiles directly to be shipped with your release? One reason is that without makefiles, you can’t run make. This means that you’re forced to run configure first, after you download and unpack a project distribution package. Makefile.in files are nearly identical to the makefiles you might write by hand, except that you didn’t have to. And they do a lot more than most people are willing to hand code into a set of makefiles. Another reason is that the configure script may then insert platform-characteristics and user-specified optional features directly into your makefiles, making them more specifically tailored to the platforms on which they are being used.

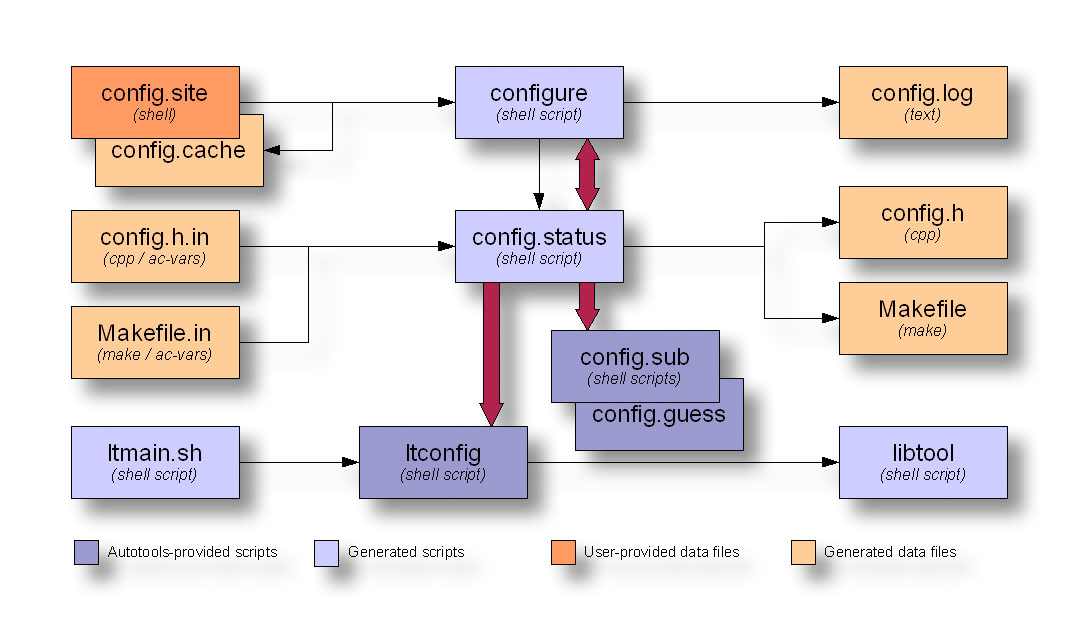

The following diagram illustrates the interaction between configure and the scripts that it executes during the build process to create your Makefiles and your config.h header file:

Figure 4: Configure script data flow diagram

The configure script appears to have this weird sort of incestuous relationship with another script called config.status. I’ll bet you’ve always thought that your configure script generated your makefiles. As it turns out, the only file (besides a log file) that configure generates is config.status. The configure script’s function is to determine platform characteristics and features available, as specified in configure.ac. Once it has this information, it generates config.status such that it contains all of the check results, and then calls it. The newly generated config.status file uses the check information (now embedded within it) to generate platform-specific config.h and makefiles, as well as any other files specified for instantiation in configure.ac. As the double ended red arrow shows, config.status can also call configure. When used with the –recheck option, config.status will call configure with the same command line options with which it was originally generated.

The configure script also generates a log file called config.log, which contains very useful information about why a particular execution of configure failed on your user’s platform. As maintainer, you can use this information to help you debug user problems. Just ask them to send you their config.log file. The problem is often in plain sight. Another nice feature of config.log is that it logs how configure was executed–which command line options were used.

From a user perspective, this could be really handy, as he comes back from a long vacation, and can’t remember what options he used to generate the project build directory. But Autoconf-generated configure scripts make it even simpler than this. If you need to re-generate makefiles and config.h header files for some reason, just type ./config.status in the project build directory. The output files will be generated using the same options originally used to generate the config.status file.

Remote build directories

A little-known feature of Autotools build environments is that they need not be generated within a project source directory tree. That is, a user may execute configure remotely, and generate a full build environment within a remote build directory.

In the following example, Joe User downloads doofabble 3.0 and unpacks it. Then he creates two sibling directories called doofabble-3.0.debug and doofabble-3.0.release. He cd’s into doofabble-3.0.debug, executes doofabble-3.0’s configure script remotely with a doofabble-specific debug option, and then runs make. Finally, he switches over to the doofabble-3.0.release directory and does the same thing, this time running configure without the debug option enabled:

$ tar -zxvf doofabble-3.0.tar.gz

$ mkdir doofabble-3.0.debug

$ cd doofabble-3.0.debug

$ ../doofabble-3.0/configure --enable-debug

$ make

...

$ cd ..

$ mkdir doofabble-3.0.release

$ cd doofabble-3.0.release

$ ../doofabble-3.0/configure

$ make

...Users don’t often care about remote build functionality because all they generally want to do is configure, make and install your code on their own platforms. Maintainers, on the other hand should find remote build functionality very useful, as it allows them to, 1) maintain a reasonably pristine source tree, and 2) maintain multiple build environments for their project, each with potentially complex configuration options. Rather than reconfigure a single build environment, they may simply switch between build directories configured in multiple different ways.

Running make

Finally, you run make. Just plain old make. In fact, the Autotools designers went to a LOT of trouble to ensure that you didn’t need any special version or brand of make. You don’t need GNU make–you can use Solaris make, or BSD Unix make if you wish (read, “if you must”).

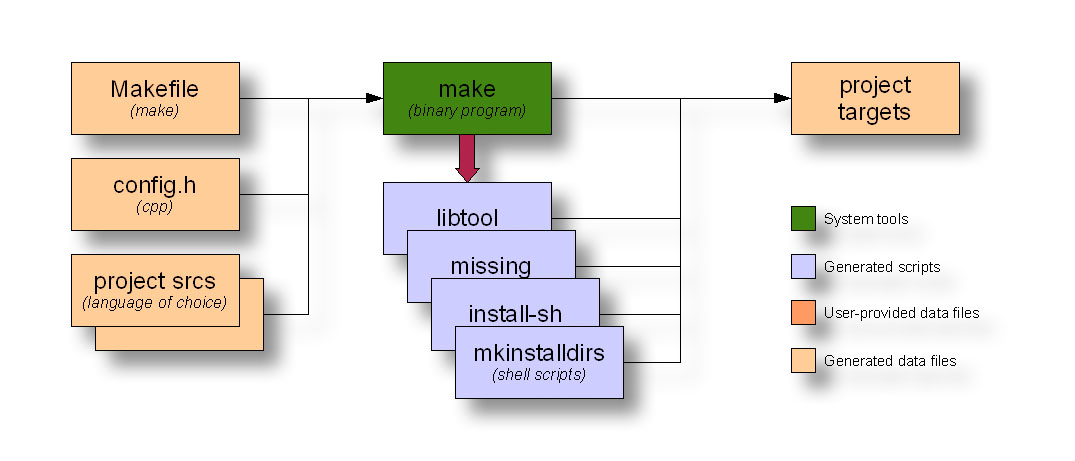

The following diagram depicts the interaction between the make utility and the generated makefiles during the build process to create your project products:

Figure 5: Make data flow diagram

This diagram shows make running several generated scripts, but these are all really ancillary to the make process.

Summary

In this chapter I’ve presented a high-level overview of the Autotools to give you a feel for how everything ties together.

In the next chapter, we’ll begin creating a hand-coded build system for a toy project. The idea is that you’ll become familiar with the requirements of a reasonable build system, and how much can be done for you by the Autotools.

Too many developers these days start out with the Autotools, not having aquired through the “school of hard knocks” the experience to know what it’s really doing for them. This can lead to frustration, and a negative attitude. In the next chapter, you’ll become familiar with the rationale for a lot of the original design of the Autotools. In understanding this background information, my hope is that any potential negative bias you may already have for the Autotools will be tempered a bit.